Меню

Social networks

May 11, 2025, 8:12 a.m.

Romanization of Bessarabia: How the ethnic map of the region was changed

Цей матеріал також доступний українською97

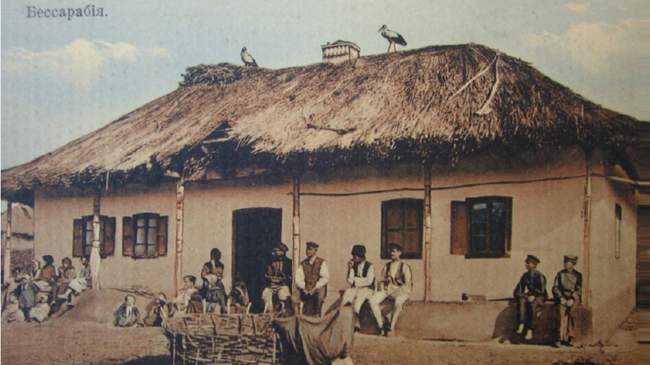

Image: Image: Moldovenii.md

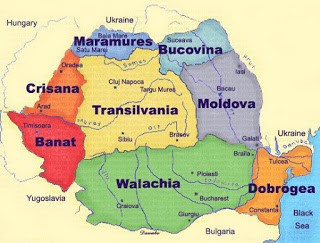

As a result of the Crimean War of 1853-1856, which ended in Russia's defeat, the Treaty of Paris was signed. According to it, the lands of Izmail and the southern part of Kahul districts (more than 12 thousand square kilometers with a population of about 200 thousand people) were ceded to the Principality of Moldova. In 1862, the Moldavian and Wallachian principalities were united into a single state, which gave impetus to the development of Romania as a whole. The primary task of the new country was to create a "united Romanian nation from sea to sea," which included the lands of Bulgaria, Transylvania, Banat, and Bessarabia. The latter was of great importance to Romanian politicians, as its accession would mean the final unification of a single Romanian nation in a single country.

Greater Romania. Source: gagauzlar.md

Initially, the Moldovan-Romanian administration abolished the old territorial-administrative structure. Instead of the Izmail district, the Izmail and Cahul cinutas were formed, which were divided into communes. In 1859, local schools were replaced by Romanian schools, where learning the state language became compulsory.

By the end of 1878, only Romanian schools remained in the region: gymnasiums in Bolhrad and Izmail, 7 four-grade schools, and 124 rural schools with 3944 students. Certain concessions were made to the Bulgarian colonists. In exchange for their loyalty, local communities were allowed to maintain Bulgarian schools. In particular, in 1867 the Bulgarian gymnasium was opened.

During the years of its rule, the Romanian authorities tried to change the ethnic map of the population in every possible way. The main form of harassment of the non-Romanian population was economic leverage. During 1857-1876, the local population was obliged to pay Romania a "state loan," a "highway tax," and other fees worth 4.2 million francs.

In 1874-1875, the Romanian government carried out a land reform. Plots that had been transferred to the village community for perpetual possession for household use by tsarist decree in 1819 were now transferred to private ownership for a purchase price. Local peasants, who suffered from the closure of the Danube ports, had to pay 80 francs in taxes annually for a tithe of land. The annual taxes per family exceeded 420 francs, which was far beyond their means.

A vivid indicator of the consequences of tax policy in the region is the publication of the Berlin newspaper Die Presse on April 13, 1876: "The last 20 years have made this part of Moldova impoverished and economically backward under Romanian rule."

Under such conditions, life in Romania for the non-Romanian population became extremely difficult. Lipovans, Bulgarians, and Ukrainians began to flee en masse to the Russian part of Bessarabia. An example of mass emigration is the Albanian population of the village of Caracurt. In 1857, 1190 people lived there, and in 1863 - 402. In addition, 931 Albanians moved to the Pryazovian villages of Hamivka and Heorhiivka.

On November 8, 1860, the Legislative Assembly of the Principality of Moldova extended recruitment to the colonists, which completely contradicted the resolutions of 1857-1858. On the same day, bloody clashes between the colonists and government troops took place in Bolgrad, killing about 20 Bulgarians.

Outraged by this attitude and incited by Russian agents in Izmail and Bolhrad, the colonists began emigrating to Russia. Between November 8 and 14, 1860, 382 colonists crossed the border.

In turn, the Russian government supported the immigrants in every way possible. On December 26, 1860, Emperor Alexander II issued a decree on the settlement of immigrants from the Danube region in the Tavriya, Kherson, and Katerynoslav provinces. Each family received 50 acres of land and 125 rubles in silver. All the benefits the colonists had received when they moved to Bessarabia in the early nineteenth century were confirmed.

In January 1860, the Ministry of State Property of the Russian Empire reported that 2,639 Bulgarian families had moved from the Principality of Moldova and received new plots of land in southern Ukraine.

The Slavic population was declared to be Russified Romanians who should be returned to their native culture. Ukrainians, Bulgarians, Gagauzes, Albanians, and Russians were classified as Slavs, who, according to Romanian officials, had no right to live on Romanian lands.

While in 1858 the Romanian researcher Ionescu de la Brad estimated the population of the Danube region at 200,000, in 1860 the Romanian government recognized the population of the region at 138-139,000.

In 1861, the Russian consul in Izmail, Maksym Romanenko, reported to the consul general in Bucharest, Mikhail Girs, that during 1860-1861, as a result of the Romanization of the region and the forced reduction of the Slavic population, more than 25,000 people left the region, including 1,500 ethnic Ukrainians and Russians, and the rest were Bulgarian colonists.

According to Russian government officials, only 15% of the population recognized themselves as Romanians in the 1850 census, while more than 75% of the population identified themselves as Ukrainians, Russians, and Bulgarians. As a result of the national policy of the Romanian government, the share of the Romanian population in Izmail district more than doubled, while the share of the Slavic population decreased from 75 to 59%.

According to Russian government officials, during the 1897 all-Russian census in Southern Bessarabia, 96.4 thousand people, accounting for almost 37% of the population, recognized themselves as Romanians; 109.5 thousand people, accounting for 45% of the population, recognized themselves as Ukrainians, Russians, and Bulgarians.

The decrease in the "Slavic race" is also explained by the separation of the Gagauz, who were recognized as such by almost 7%. If these groups are combined, their share will still be smaller (52% in 1897 vs. 59% in 1859).

Thus, the Romanization of the region was a clear success, and after the region was annexed to Russia, the Moldovan-Romanian ethnic group demanded to preserve their cultural autonomy and property rights. Therefore, the Russian government was forced to pursue a cautious policy and preserve the internal self-government of the region.

Indeed, the Izmail district remained the only one where the Romanian system of self-government was preserved until 1914. Attempts by imperial officials to carry out cautious Russification were met with resistance from both local elites and the rural population. "Mom is Russian, dad is Russian, and Ivan is Moldovan," was the rather cynical reaction of local peasants to Russification.

The second stage of the Romanization policy

As a result of the events in Russia in 1917-1922, some of its territories were annexed by neighboring countries. Southern Bessarabia suffered a similar fate. With the support of the pro-Romanian government of Bessarabia, Romanian troops occupied the southern part of the province, which belonged to the Ukrainian People's Republic, in January 1918. A new stage of Romanian rule began, lasting until 1940.

Romanian occupation troops. Source: bessarabiainform.com

The Romanian authorities pursued a similar policy in the Moldovan-Ukrainian lands of Bessarabia and Bukovyna. The goal of all measures was the forced Romanization of the population and the transformation of the occupied lands into a part of Greater Romania.

In order to strengthen the position of the Romanian authorities, in December 1918, a decision was made, confirmed by a royal decree of January 29, 1919, to establish the Central State Security Service. An important part of the security service's work was to monitor border violations and warn against Bolshevik and Ukrainian agitation in Northern Bukovina and Bessarabia.

In order to eliminate the conditions for agitation, it was planned to identify propagandists and move Ukrainian employees to the interior of Romania. Censorship of the press and correspondence was to play a corresponding role, designed to control possible socialist and communist agitation.

In order to establish the occupation regime, the Romanian government created a rigid system of state administration in Bessarabia, dominated by monarchical forces that eventually led to the fascist regime.

County prefectures and volost prefectures were established. They were under the jurisdiction of the Romanian Ministry of Internal Affairs. The prefect was the highest representative of administrative power in the county. He led the police and gendarmerie in the fight against the revolutionary movement, and supervised the activities of all state institutions, charitable and public organizations.

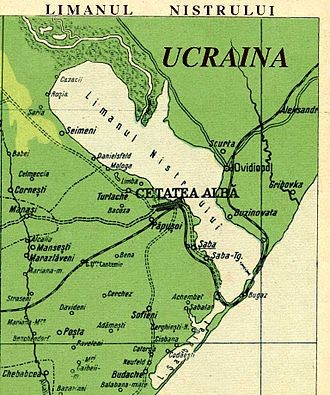

In towns and villages, there were primarii (mayor's offices - ed.) headed by primarii. Permanent missions served as executive bodies of the primaria. Communal consiliums functioned under the mayors as an advisory body. The mayors of the cities of Izmail and Cetatia Alba(Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi) were subordinated to the Director General of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Bessarabia, from December 16, 1922, to the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Romania, and from August 1938, to the Dniester and Lower Danube cinut.

Akkerman on the Romanian map of 1927. Source: akkermanika.org

The Romanian government, contrary to the 1923 Constitution, which proclaimed the equality of all nations and recognized the right of national minorities to their language, culture, and religion, pursued a policy of Romanization. Ukrainians, Bulgarians, and representatives of other non-Romanian ethnic groups could not work in administrative bodies. Public events in Ukrainian and Russian were prohibited. Schools were closed, and some were translated into Romanian. All teachers who did not accept Romanian citizenship and did not speak Romanian were fired.

Ukrainian reading and theater groups were closed. Periodicals were published only in Romanian. The adoption of Romanian citizenship with a change of surname and nationality was strongly encouraged.

The situation in the Comrat lyceum was indicative. As early as December 1921, education in Bujak was translated into Romanian. However, on December 5, 1929, 6th grade students refused to attend classes in Romanian. Students in grades 3 and 5 joined the children's strike. The children's strike was supported by teachers on December 7 and 12. The teachers were disciplined for this.

Former Prime Minister Alexandru Vaida-Vojvoda was forced to say: "The tsar's whip was bad, but it was a joke compared to the whip that now reigns in Bessarabia."

Identifying the disloyal. Image: naspravdi.info

According to the 1930 census, compared to 1897, the Romanian population increased: in Akerman - from 0.8% to 14.6%, in Izmail - from 7.1% to 19.2%, in Bolhrad - from 5% to 18.5%, in Reni - from 37.6% to 56.6%. The Ukrainian and Russian population decreased in Izmail from 72.3% to 71.1%, in Bolhrad from 13.8% to 12%, in Kiliya from 58.2% to 53.7%, in Reni from 37% to 30.2%, and in Akkerman from 74.2% to 69.3%. It is clear that such demographic changes could not have occurred in 33 years. The above data were the result of falsifying the ethnic origin of citizens.

In 1927, the writer Ion Petrovich wrote in the newspaper Universul (Bucharest): "the Russians failed to Russify Bessarabia in 105 years, we managed it in less than 4 years. National minorities, what are your rights based on? Did you suffer for your homeland? You are migratory birds. You have no historical rights."

In the spring of 1938, the Romanian government finally banned any use of another language. Services in Bujak were held only in Romanian, and postcards in another language were returned to the senders.

Increased social and national oppression drove non-Romanian people to the Ukrainian SSR and Europe. Between 1918 and 1928, 300,000 people left Bessarabia without permission. The emigration of Gagauz and Bulgarians was quite significant. According to incomplete information, more than 20 thousand Gagauzes left the region, mostly emigrating to South America.

The Romanian occupation regime sharpened socio-economic and national contradictions in Bessarabia to an unprecedented degree, and thus encouraged the political forces of the region to continue their struggle for social and national liberation.

In September 1924, the Tatarbunary uprising broke out, involving about 6,000 residents of Budzhak. The uprising was suppressed, but the underground struggle continued until June 1940, when the Soviet army completely occupied Bessarabia and Budzhak. The period of Sovietization began, which significantly changed the ethnic map of the region.

Андрій Шевченко